-

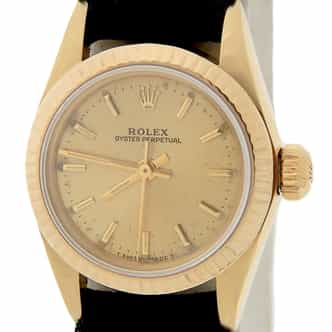

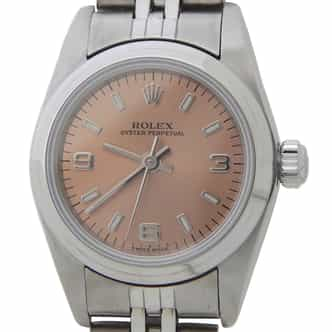

Your Price:

$4,999.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

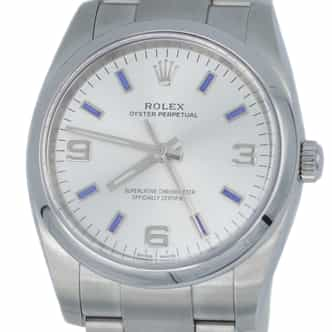

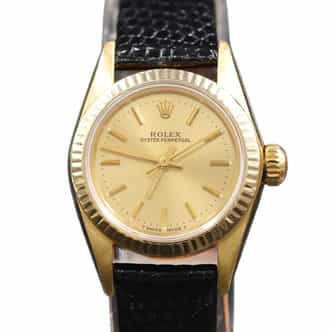

Your Price:

$6,499.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

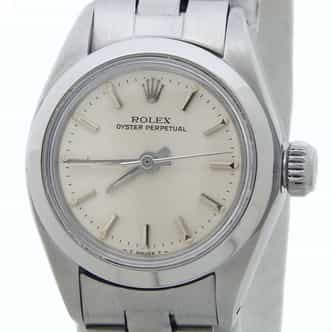

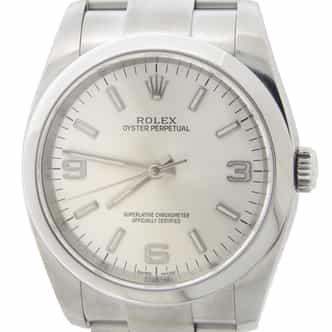

Your Price:

$2,499.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

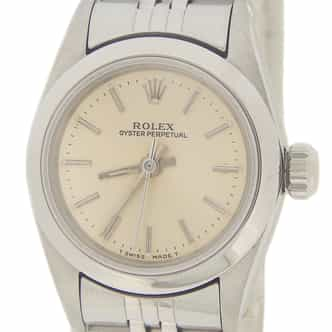

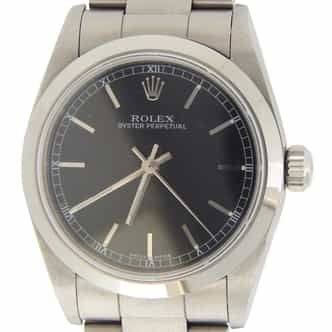

Your Price:

$3,999.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$2,599.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,699.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,999.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$2,599.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,699.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,599.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$5,599.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

Your Price:

$3,999.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$4,199.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$7,899.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

Your Price:

$5,999.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

Your Price:

$6,499.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

Your Price:

$4,099.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$4,799.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,899.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$5,299.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

Your Price:

$5,299.98 $500 | Coupon: JULY500 -

Your Price:

$3,499.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,799.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$4,849.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$3,599.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350 -

Your Price:

$4,799.98 $350 | Coupon: JULY350