300 Years Old and Accurate to the Second

In the 18th Century it was seen to be the ravings of an old man.

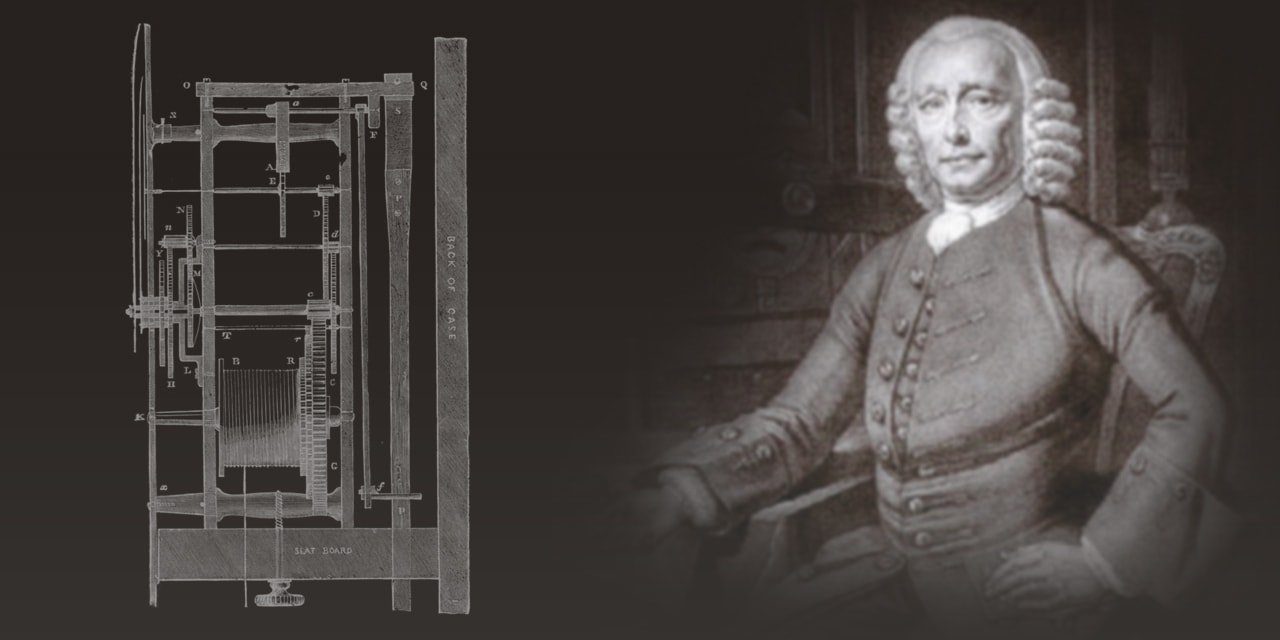

That man was John Harrison.

John Harrison, born in 1693 to a Lincolnshire carpenter, is best known as the man who solved the problem of longitude. The Royal Navy had lost many ships at sea because although latitude could be determined by the height of the sun, longitude was more difficult to determine.

Harrison thought the problem could be solved, and the Longitude Prize of £20,000 that went with it won, by designing a clock carried at sea that could keep time to within about a minute over 50 days. By knowing the time the ship had been at sea, and knowing local time from the height of the sun, it would be possible to determine longitude accurately, as local time is one hour ahead for every 15 degrees of longitude eastwards and one hour behind for every 15 degrees west.

A pendulum clock designed 300 years ago has been certified as the world’s most accurate in its class by time-keeping experts from Guinness World Records.

The pendulum clock design was created in the the 18th century – but never built, and a book describing the technique was dismissed as the ‘ramblings’ of an old man.

Its creator, famous clock designer John Harrison had boasted that it would be not gain or lose a second in 100 days – a preposterous idea at the time and scoffed at by many.

But when horology experts at Greenwich’s Royal Observatory built the clock from Harrison’s design within a perspex case, and monitored it against the a radio controlled clock, he was right.

Harrison is world-famous as the inventor of the first clock accurate enough to permit British ships to navigate past the Equator, chronicled in the bestselling book Longitude (1995).

‘It was a claim that Harrison made and a claim nobody believed because the best clocks of the day could not do better than about a second a week, if they were lucky,’ said Jonathan Betts of the Royal Observatory.

‘So the idea that somebody was going to keep time to an accuracy of a second in a 100 days was preposterous.

‘It was only in the 20th century that people thought that Harrison may have been right.

‘As soon as we set the clock running it was clear that it was performing incredibly well, so then we got the case sealed because nobody was going to believe how well the clock was running.’

The clock, known as the Martin Burgess Clock B after its modern-day maker, was set ticking a year ago but it soon became apparent it was going to be a record-breaker, which is why the Observatory placed wax seals on its Perspex case for a certifiable 100-day trial.

“Today sees the culmination of a trial within a trial,” said Jonathan Betts, a member of the Antiquarian Horological Society and senior specialist in horology at the Royal Observatory. “As soon as we set the clock running it was clear that it was performing incredibly well, so then we got the case sealed because nobody was going to believe how well the clock was running.” In his later years, Harrison had left instructions on how to build the clock in an obscure book, which was so hard to read it became known as “the ramblings of superannuated dotage” by later horologists.

The clock is based on Harrison’s designs but used modern materials, chiefly duraluminium and invar (a nickel-iron alloy). The mechanism, however, is from Harrison’s instructions.

It may be approaching the ‘perfect’ clock, but there will always be tweaks and refinements that can be made. Who knows what the future holds for timekeeping.

— Featured and Body Photo Credits: Wikipedia (cc).