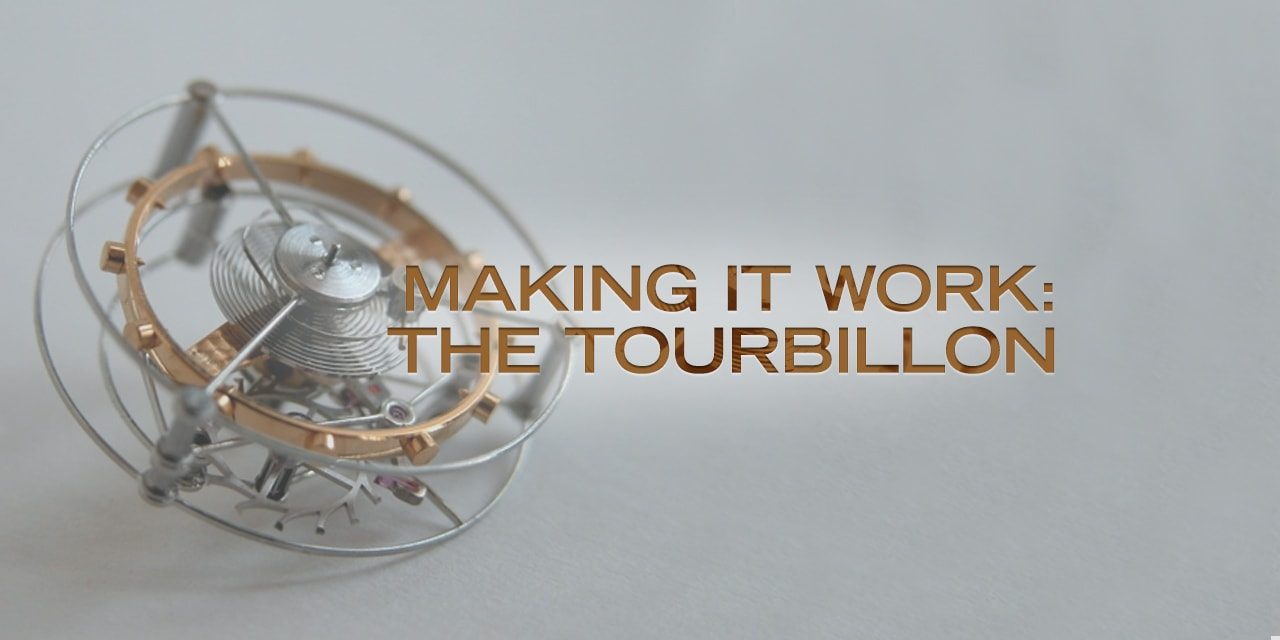

Making it Work: The Tourbillon

So far in this mini-series exploring the various components that go into a modern watch movement, we have looked at mainsprings and escapements; two elements without which a wristwatch just could not work.

This time we’re going to examine one which is, for all intents and purposes, expensively superfluous—the tourbillon.

What is a Tourbillon?

If you take a look at the average price of tourbillon watches you will see just how much more pricey they generally are than non-tourbillon models. To some it can seem as if the contraption doesn’t do much to justify the extra expense until you remember the tourbillon was invented solely to fight against one of the fundamental forces of nature; gravity.

Gravity, like magnetism, is no friend to mechanical watches. Even though it is a relatively weak force, it is still more than strong enough to create a drag effect on some of the smaller components in a movement, inducing timekeeping errors if a watch is left in one position for too long—what are known as positional errors.

Essentially, a tourbillon keeps the most important constituents in a perpetual state of motion to negate these positional errors, regardless of whether or not the watch is being worn.

How does it do that? By containing the escapement, balance and hairspring inside a cage which rotates through 360°, once every minute. The cage is meshed to the gear train which means that, as long as the watch is wound, the tourbillon will turn.

Hang On!

What you might well be asking yourself right about now is, how could a wristwatch stay in one position so long that gravity had time to affect its accuracy?

It’s a good question and one which can be answered by telling you just when the tourbillon was invented.

The mechanism came into being all the way back in 1795, devised by the legendary Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Known as the father of watchmaking, as well as the tourbillon Breguet is also responsible for the rotor we find in automatic watches, the overcoil on the balance spring which bears his name and (possibly) the first perpetual calendar complication on a wristwatch, among many others.

All of those were to follow, however. In 1795, we were still some years away from the first ever wristwatch (that came along in 1810, invented by *checks notes* oh, Breguet).

At the time Breguet designed the tourbillon, pocket watches were the only true portable timepiece, worn pretty much exclusively by men. And because the watches spent the vast majority of their time in one of two positions; either vertical in a vest pocket, or else lying flat on a table, they were not physically moved around enough in the course of an average day to overcome gravity’s effects. Hence, the tourbillon was almost essential for timekeeping precision.

Today though, you will find tourbillons fitted to many very high end (and some not so high end) wristwatches. And, because they are in almost constant motion as a matter of course, these days the tourbillon is more a cross between a status symbol and an illustration of the watchmaker’s art than a necessity in any practical sense.

The Different Types of Tourbillon

As you might expect, what with the technology being well over two centuries old, there have been more innovations made to the tourbillon over the years.

Multi-Axis Tourbillon

This is where we dive into the haute-iest end of haute horology. Whereas standard tourbillons rotate around one axis (a fearsome enough feat already for a manufacture) double and triple-axis (otherwise known as tri-axial) tourbillons, rotate around two or three axes respectively.

The tri-axial especially are absolutely spellbinding, with the tourbillon cage spinning and pirouetting in all directions, usually at different rates of rotation. Watching them, you can see where the mechanism originally picked up its name; tourbillon is the French word for ‘whirlwind’.

Check out Girard-Perregaux’s latest masterpiece, the Minute Repeater Tri-Axial Tourbillon to see one in action. Even better, if you have a spare $550,000 lying around, you can pick one up for yourself.

Flying Tourbillon

A traditional tourbillon is mounted in a watch with two bridges, upper and lower, securing it from above and below.

The flying tourbillon, invented by Alfred Helwig in 1920 while working for Glashütte, on the other hand, is only mounted from underneath so the mechanism looks like it’s hovering.

An even more demanding test of technical prowess, you will find flying tourbillons in works from manufactures as wide-ranging as Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet for six and seven-figure sums, all the way through to the extraordinary Tourbillon 1 from Swiss independent Horage, retailing for around $8,000.

A Source of Debate

While it isn’t the most controversial subject in the industry, there has long been spirited discussion over whether the tourbillon qualifies as a complication or not.

Purists tend to say no, with many believing that as it doesn’t present any additional information in the way, for instance, a moonphase or a chronograph does, it is better described as a regulating device.

Others believe that, as the tourbillon is a challenging mechanism to create and is not a necessary part of the movement, it can be described as a complication.

The folk over at Vacheron Constantin obviously believe so, as a three-axis tourbillon counts as one of the 57 complications they claim for their ref. 57260, the most complicated watch in the world.

Whatever your opinion, there is no denying that the tourbillon represents one of the highest achievements in watchmaking. The level of microengineering required to craft and execute such a device is staggering. And while they may not be of any real-world use in wristwatches, seeing them at work is one of the great joys of horology.

Featured Photo: Simon Schaller (Benutzer: simusch, eigenes Bild), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.