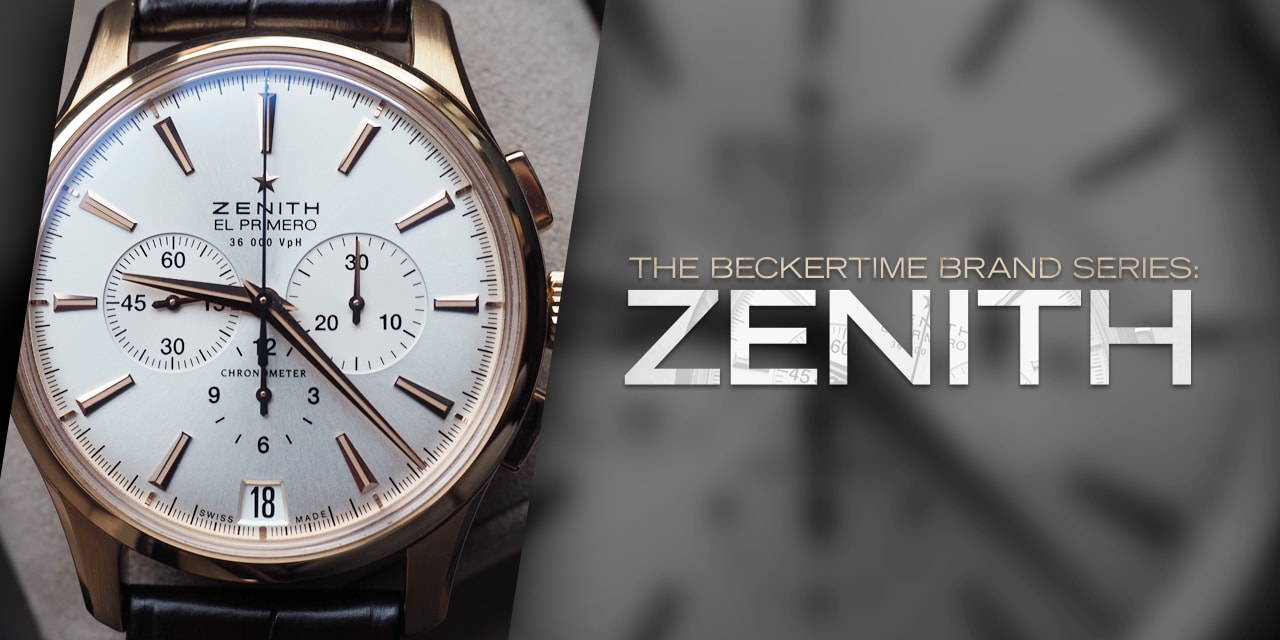

The Beckertime Brand Series: Zenith

In business since the middle of the 19th century, Zenith is today something of an oddity; a manufacture perhaps best known for one of their movements rather than the watches themselves.

Truth be told, the brand has always done things a little differently. They were the first Swiss watchmaker, for instance, to break from the deep-rooted ‘établissage’ system in the country and bring all of their component manufacturers under one roof. So, it can be said, that it was Zenith who pioneered the notion of mass production to horology.

They can also, arguably, lay claim to having created the very first pilot’s watch, worn by Louis Blériot on his maiden air crossing of the English Channel in 1909.

These days the Zenith catalog is heavy on the chronographs, as you would expect given their heritage, but they cover a wide range. At one end, the Chronomaster collection offers a glance back at some of the brand’s most successful models of the ‘60s and ‘70s. While at the other, the state-of-the-art Defy series has been among the most disruptive innovations in horology since about 1675.

In all, this is a manufacture at the top of its game and its reputation has rarely been higher.

Below we take a closer look.

Zenith Watches History

The company which would go on to become Zenith was established in Le Locle, Switzerland, in 1865. Founder Georges Favre-Jacout was a mere 22-year-old at the time, fresh from completing his watchmaking apprenticeship, but determined to find a better and more productive engineering route.

The process at the time involved numerous separate manufacturers building individual watch components, usually in their own homes, which were collected by a central body known as the comptoir. That comptoir would then give all of those elements to yet another independent watch assembler to construct the finished piece.

While the system had been in use for many years, its limitations and inefficiencies were obvious and so Favre-Jacout went about creating an integrated structure for his business, with all the major constituents being built in one factory.

So, with the world’s first modern manufacture, Zenith had an enviable competitive edge. The brand launched its debut pocket chronograph in 1899 and the following year, Favre-Jacout won the gold medal at the Paris Universal exhibition.

Zenith In The 20th Century

With Zenith’s industrialized production plant growing steadily, the watchmaker continued to make strides throughout the early to mid 20th century.

At the beginning of the 1900s, the company began building aircraft cockpit instruments and by 1909 had become recognizable enough that French aviator, Louis Blériot chose a Zenith wristwatch to accompany him as he braved the dangers of crossing the English channel in his monoplane, the Blériot XI.

It was a move which saw the brand, officially adopting the Zenith name in 1911, become one of France’s most popular watch manufacturers. When WWII broke out in Europe in 1939, the French Air Force enlisted their help to produce an aircraft clock, leading to the creation of the Type 20 Montre d’Aéronef. The hand wound chronometer featured the sort of large, luminous hour markers we now think of as standard in a pilot’s timepiece, and a deeply knurled bezel to make it easier to grip while wearing gloves.

However, their biggest breakthrough to date occurred postwar. In 1948 Zenith released the Calibre 135, a chronometer movement for wristwatches. The mechanism, with its small seconds sub dial, would eventually win no fewer than 235 awards for design and accuracy. In fact, Zenith itself stands as one of the most decorated watchmakers in the industry, with more than 2,400 honors for timekeeping and innovation.

Zenith, the Quartz Crisis and the El Primero

Zenith continued to flourish well into the middle of the century. But trouble was looming.

In 1960, they unveiled the Caliber 5011K, a record-breaking movement which would be used to drive marine chronometers, table clocks and even pocket watches. The brand also fitted the caliber into a limited edition aviator’s wristwatch, the Pilot Montre d’Aéronef Type 20.

But their biggest success of the decade came right at the end. One of the last great unmet challenges of horology, a self-winding chronograph movement, was being tackled from three different directions at once. In Japan, Seiko were at work on what would become the 6139. Just down the road from Zenith a consortium, consisting of Heuer, Breitling, Hamilton-Buren and Dubois Depraz were also keeping busy. Calling themselves the Chronomatic Group, the result of their efforts would eventually be the Calibre 11.

As for Zenith themselves, they had actually started working on the project as early as 1962, with the hopes of unveiling their automatic chronograph in 1965 to commemorate the company’s centenary. 1965 came and went with no caliber, as did every other year up to 1969, when all three competitors unleashed their creations more or less simultaneously.

Who was the outright winner is a matter of conjecture, even today. Certainly though Zenith’s El Primero (meaning ‘the first’, cheekily) was the most impressive. Firstly, it was an integrated movement, unlike the Chronomatic Group’s modular Calibre 11. And, unlike Seiko’s 6139, the El Primero was a very high beat mechanism, vibrating at 36,000vph, leaving it able to measure increments as low as 1/10th second.

However, as remarkable as it was, by the end of the ‘60s Zenith, and the entire Swiss industry, had much more to worry about.

It is ironic that one of the most significant conundrums in mechanical watchmaking was solved in exactly the same year as the first quartz movement was released commercially.

The sudden influx of cheap, disposable and absurdly accurate watches from Japan and America caught Switzerland’s traditional maisons pretty much unawares. Before long, the industry had been brought to its knees, with more than two-thirds going bankrupt by the end of the 1970s.

Zenith was also hit hard and was forced to sell out to the Zenith (coincidentally) Radio Corporation in Chicago in 1971. Inexplicably, their new owners ordered the brand to not only concentrate exclusively on producing quartz watches, but to sell all their existing machines and tooling for scrap. As if that wasn’t shortsighted enough, they also demanded that every piece of documentation and instructions on how to build their mechanical movements be burned.

The reason the El Primero still exists today is all down to one engineer, Charles Vermot, who spent months dismantling his machines and hiding them in the attic of the firm’s Ponts-de-Martel factory, where they would stay hidden, along with all the necessary literature, for more than a decade.

Zenith Back in Business

By 1978, the public’s love affair with quartz had cooled to such an extent that Zenith fell back into Swiss hands.

In amongst the artifacts Vermot had squirreled away was a massive backlog of unassembled El Primero calibers, which were sold to Ebel in 1981, bringing much needed funds into the business.

In 1984, the production line was able to get up and running again without the need for massively expensive reinvestment from Zenith’s new owners, so when Rolex came calling just a few years later looking for a power plant for their rejuvenated Daytona, the brand’s books returned to rude health.

A few years later, they had grown big enough to attract the attentions of LVMH, who brought the company under their umbrella in 2000.

With the acquisition, Zenith truly entered the modern age, demonstrated perfectly with their 2017 release of the Defy Lab concept.

This extraordinary engineering feat completely reinvented watchmaking convention, incorporating more than 30 traditional components, such as the balance, balance wheel, balance spring and escapement, into one single silicon module just 0.5mm thick. Working on the principles of compliant mechanics, the Defy Lab’s caliber, the ZO 342, beat at a frenetic 108,000vph, or 15Hz which, even by Zenith’s own standards, was an incredible speed. Not only that, but the movement had a reported accuracy of around 0.5 seconds a day.

Only 10 units of the Defy Lab were made and all sold privately to collectors. However, the success of the technology (the oscillator won the Innovation prize at the 2017 Grand Prix d’Horologerie de Genève) led to the range being put into full production and the first commercial release arrived in 2019 in the shape of the Zenith Defy Lab Inventor.

The 44mm open worked model with its integrated bracelet actually got, believe it or not, a faster movement—the Caliber 9100 beating at 129,600vph!

Sine then, the range has grown exponentially, and now includes a number of chronographs, the Extreme and 21 series. These, thanks to their use of a second, high frequency escapement running at 360,000vph, can measure down to 1/100th second, an incredible achievement for a mechanical watch.

Zenith has had a turbulent history, but are very much at the top of their game at the moment. The intelligent blend of the vintage and absolute cutting-edge throughout their catalog holds temptations for watch lovers of all description, and their heritage is hugely impressive.

A more knowing alternative to the usual Swiss suspects, the Zenith name holds a real gravitas among collectors.

Featured Photo Credit: mikewalles with a (cc) Pixabay License and BeckerTime’s Archive.