The BeckerTime Guide to the Rolex Daytona

There are any number of great stories from the world of horology.

You can take your pick from the origins of Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak and its designer’s 12-hour deadline, the otherworldly punishment rained down by NASA on Omega’s Speedmaster to ensure it was up to the job, modern Hollywood royalty’s rocky relationship with Panerai and dozens more.

But if you’re a sucker for a good rags-to-riches tale, then the lifespan of Rolex’s now-legendary Daytona should give you the feel goods. From a commercial non-starter to the most sought-after and alluring timepiece on the planet in a little over 50-years, the Cosmograph still exists in an arena of desirability all its own.

A Little History

Rolex were uncharacteristically late to the party when it came to chronographs.

Although we can trace their first attempt back to 1935 and the ref. 2508—a two-register, two-button watch powered by a Valjoux 22 movement—initial efforts were tentative at best.

The earliest models were housed in non-Oyster cases even though that industry-disrupting innovation had been in existence for a decade by then, and during the ‘40s the portfolio even contained several square-cased pieces, namely the likes of the ref. 3529 and ref. 8206.

However, although their opening steps were indeed faltering, Rolex’s reputation still carried them through. Another of those great watch history stories tells us that it was some of these incipient chronographs which the brand distributed to captured allied POWs for free during WWII and aided in many of the most well-known escape attempts.

It was not until the 1950s that we hit on that species of Rolex chronograph which would go on to be known as the ‘pre-Daytonas’.

These, all falling within the 6000 reference number range, benefitted from waterproof Oyster cases, with some, such as the ref. 6036 and ref. 6236, also coming with triple calendar complications—the renowned and utterly wonderful Dato-Compax.

But it was during this era that competition between manufactures to produce the finest chrono was at its fiercest. The first Heuer Carreras and Breitling Top Times emerged around the same period, along with an aforementioned specimen which would alter the game completely. When Omega had the brainwave to move their Speedmaster’s tachymeter scale on to the bezel rather than printing it around the edge of the dial, thus freeing up valuable real estate and granting a level of legibility never before seen, the model suddenly became the name in mechanical stopwatches.

Rolex’s final pre-Daytona piece was the ref. 6238 which, with the exception of its smooth bezel and inbound tachy scale, set the blueprint for what was about to land. A genuine Bond watch, appearing in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service on Lazenby’s wrist, it was a perfect marriage of sport and dress watch styling and its production from 1962 to 1969 meant it actually ran alongside the debut reference of what would eventually be christened the Daytona, the ref. 6239. For the first few years though, it was known by another name; the Cosmograph Le Mans.

While the shift from Le Mans to Daytona in 1965 is easy enough to explain (Rolex simply had a larger market in America and wanted to appeal to them), the origin of the Cosmograph name has been a point of speculation amongst collectors for many years. The most obvious answer revolves around the space race which by this time, 1963, was in full flight. NASA had been formed a mere five years earlier and it was no secret there was going to be a need for a standard-issue astronaut watch. It is thought Rolex chose the astronomic-sounding moniker in an effort to attract the attention of buzz-cutted higherups at the organization. As we know now that didn’t happen, the irony being that the Daytona was passed over in favor of the Speedmaster, a watch designed from the outset exclusively for the racetrack and launched before NASA was even established, while Rolex’s unsuccessful shot at ingratiating themselves with the agency left them with the most famous racer’s companion of all time.

That, however, was going to take a while; a quarter of a century, to be precise. The nine references which make up the first generation of the Daytona were, to put it mildly, a flop.

The watches themselves were some of the best chronographs on the market. Good-looking, robust and highly accurate, their one and only downfall lay in their movements. All were powered by Valjoux calibers, which were also the best in the industry. The problem was that they were manually-wound.

The 1960s was a period of enormous technological progress in all fields, not least horology. The first inklings of quartz and electronic timepieces were becoming known and Rolex’s own invention of the Perpetual movement meant that the bare minimum customers expected was a watch they didn’t have to remember to wind

every day. And while the automatic chronograph wouldn’t be realized until the end of the decade, if people wanted a well-proven and thoroughly tested chrono, they were going to get the one astronauts trusted their lives to.

As a result, first gen. Daytonas which now trade for sums often counted in the six, seven and sometimes even eight figure range, either sat on dealers’ shelves or else were given away for free as incentives for clients to purchase other watches.

How The Turntables

Of course, the solution was obvious. But even though the self-winding chronograph conundrum was solved from three sides in 1969, it would take a further 20-years before Rolex was able to take advantage.

Swiss brand Zenith, in competition with countryman consortium the Chronomatic Group and Japan’s Seiko, developed their own take on the automatic chrono movement with the El Primero. Unfortunately, they went into receivership soon after, one of the earliest but by no means only victims of the Quartz Crisis.

Happily, they returned to business by the 1980s and due to the extraordinary nerve, foresight and resilience of chief engineer Charles Vermot (Google him and enjoy) were able to pick up where they left off with their ground-breaking movement.

Before long, Rolex came knocking, in the market in a huge way for a new engine for their second generation Daytona. The deal the two marques signed still stands as one of the biggest in watchmaking history, the upshot being that in 1988, a refreshed Cosmograph hit the streets…and so began a complete turnaround, not only for the watch, but for the industry in general.

The commonly referred to Zenith Daytonas, powered by a heavily reworked version of the El Primero christened the Cal. 4030 by Rolex, have been credited with kicking off the entire vintage watch collecting industry.

The iteration landed with impeccable timing, just as the public was falling out of love with the cold blandness of quartz and were once again clamoring for the artfulness and craftsmanship of traditional watchmaking.

Rolex, simultaneously, had repositioned itself out of necessity as more than the purveyor of handsome and well-made timepieces but as the ultimate aspirational lifestyle brand.

This new chronograph, beefed up and adapted for a modern audience and with the advantage of a self-winding movement, soon became the definition of the must-have accessory. Yet, with its caliber supplied by an outside concern and with those delivered still needing to be modified to Rolex’s own specifications, turnaround was painfully slow and waiting lists soon began to lengthen to ridiculous proportions. Those not prepared to delay or offer premiums to jump the queue started to scour for earlier models instead and found the first generation suddenly very appealing, their opinion of the once-impossible to sell watches not hurt one bit by its association with a certain demonically charismatic superstar. An Italian magazine’s front cover featuring Paul Newman prominently displaying his ref. 6239 was all it took to elevate the former pariah into the stratosphere. After that, interest in many other of the greatest hits from yesteryear, from Rolex and other brands, also hit never before experienced heights.

The Daytona’s subsequent path was then mapped out for it. The obvious next stage was for Rolex to develop its own movement, which happened in 2000. The Cal. 4130 was a much stripped back upgrade on the El Primero, the first of the brand’s calibers to be fitted with the proprietary Parachrom Bleu hairspring and the one which completed the set; now, every single engine in the portfolio was made in-house.

The watches they drove broke new ground for levels of demand and popularity. This third generation, and in particular the steel models, changed hands on the preowned market for many times their official price, reaching a peak in 2022 when the stainless ref. 116500LN—retailing at $14,000 or so—commanded $45K-$50K at a minimum.

The current generation, with updated Cal. 4131, refreshed case and bezel, and a lightly retouched dial, came out in 2023. It too exploded onto the preowned scene, briefly reaching similar wallet-busting numbers as its predecessor before returning to more rational levels.

But the watch itself remains one of those pieces lusted after from all corners of the collecting community, a piece Rolex doggedly refused to give up on in its troubled youth and which has now, at long last, repaid their commitment to become an undeniable icon; described by many as the most important sports watch ever made.

But which one is right for you?

If Money Really is No Object

The Rolex Daytona ref. 6239

Not only was the ref. 6239 the first ever true Daytona, it was the one responsible for the exalted status the watch as a whole enjoys today.

Arriving in 1963 to a wave of indifference, the reference was issued in either steel, 14 carat or 18 carat gold with its bezel’s engraved tachymeter scale calibrated first for 300 units/h, then later 200 units/h.

Its pump style chronograph pushers meant it was not water resistant and so the watch carried no ‘Oyster’ designation anywhere, nor did it have even a ‘Daytona’ inscription until 1965. Three different movements were used during its six-year run, all from Valjoux; the 72B, followed by the 722 and the 722/1.

However, that is all by the way. The ref. 6239’s real story revolves around its dial. There were several different colors issued as standard, the steel models getting a choice of cream, silver or black, the gold versions with either black or gold. All, in a major difference from the pre-Daytonas, received contrasting color sub dials to aid legibility.

But there was another type of dial which could be specified. Made by Singer, the so-called Exotic dials featured an unusual three-color setup, either Panda or reverse Panda style, with Art Deco-esque detailing on the totalizers and a red minute track. Wildly unpopular, even by first gen. Daytona standards, estimates put the ratio of regular models to Exotic dialed pieces produced at about 20:1.

As a result, they were and still are rare and that alone would make them highly valuable. But it was the fact that it was an Exotic Daytona which caught the eye of Joanne Woodward as she searched for a gift for her husband, Paul Newman to celebrate the beginning of his motor racing career that lifted the entire thing to previously undreamt of heights.

That ref. 6239 Newman wore on the cover of the Italian magazine did indeed have an Exotic dial. Consequently, when the mania really kicked off, they were immediately rechristened the Paul Newman Daytonas.

Nowadays, even poorly looked-after examples can’t be had for less than $150k, whereas non-Exotic models usually start at around $50k or so.

And Newman’s own watch? That still holds the record for most expensive Rolex ever sold at auction when it went for $17.8m in 2017!

If You Want the Best Value Daytona

The Rolex Daytona ref. 16523

Fortunately you don’t actually have to rob several banks to acquire a Daytona if you don’t want to.

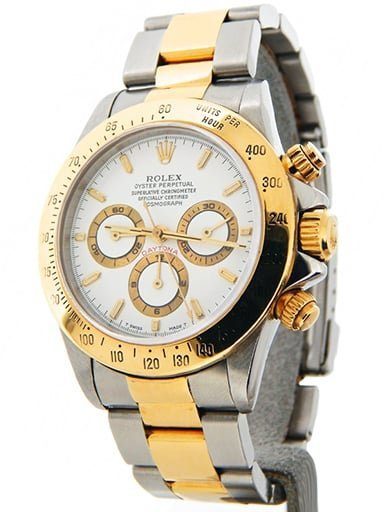

The Zenith Daytonas, the second generation which ran from 1988 to 2000, represent the entryway into ownership, and of them, the Rolesor versions are the most attainable.

It was the first time the watch was offered in Rolex’s proprietary mix of metals, with steel making up the case and outer links on the bracelet, with the bezel, crown and inner links all forged in gold. It is a striking look on an already attention-grabbing creation and it came with an intelligently thought out selection of dials designed to make the most of the tones on show.

With a white face, the ref. 16523 becomes a perfect summer’s day watch, all light and airy, while a black dial quietens it back down nicely. A champagne face gives a hint of opulence and the grey option perfectly matches the steel elements for some understated class.

Inside, the movement is faultless, derived from one of the most famous calibers ever built and modified by Rolex’s industry-leading engineers. Although the frequency was reduced from the El Primero’s originally frenetic 36,000vph (able to time down to 1/10th second), the Cal. 4030 is still a fantastically capable engine.

Best of all, this gem of a watch can be bought these days for as little as $14,000, standing it in good stead as perhaps vintage collecting’s best bargain.

If You Want the Once Unattainable

The Rolex Daytona ref. 116500LN

We spoke about the ref. 116500LN (the LN stands for Lunette Noir, or Black Bezel) before and hinted at just how in demand the steel third gen. Daytona was following its 2016 launch.

Trying to buy one at your local Authorized Dealer was likely to get you greeted by polite refusal if you were lucky or abject derision if you were not, but the result would be the same; unless you, A. had spent an enormous sum of money with said dealer in the past or, B. saved the life of their child or beloved pet or C. shared the same mother, you were not going to get one through official channels.

Rumors of each AD being sent just one or maybe two to sell per year circulated and were probably true, leading to waiting lists which were up to 10-years long at the height of the demand.

That, of course, led to astronomical premiums on the secondary scene and made professional watch flippers very happy.

Today, with the release of the updated iteration, things have calmed down considerably. The watch that money couldn’t buy has dropped dramatically to a start point of around $22,000 to $25,000 for models in excellent condition.

Obviously, that is still by no means cheap, but then you are getting an awful lot of watch for your money.

It is no hyperbole to say that the ref. 1165XX generation of the Daytona were among the best chronographs ever made, from any manufacture. The movement, the Cal. 4130, a five-year labor of love, featured a vertical clutch for highly accurate, judder free stops and starts. The ref. 116500LN’s black bezel was the first time the watch received a Cerachrom surround and the watch’s entire visual exuded a sort of robust elegance which made it the perfect allegory for the thrills and glamor of its natural home; the racetrack.

So, while the reference still represents a healthy investment of anybody’s money, and always will, there has never been a better time to get your hands on one.

Featured Photo: BeckerTime’s Archive.